Matt Ferraro

What is the Inverse of a Circle?

In a word, this:

(Mouse over to see a circle and its inverse)

In this post we’ll try to make sense of what we’re seeing, and try to understand what it means to invert a circle!

Table of Contents

- Inverse of a Real Number

- Inverse of a Complex Number

- Conformal Mappings

- Inverse of a Circle

- Enriching the Structure of a Circle

- Rotations on the Riemann Sphere

- Digging Deeper

- Contact me

Inverse of a Real Number

For any number we think of the inverse as whichever number yields:

For real numbers this is easy:

Qualitatively, the inverse of a big number is a small number and vice versa. There are two special numbers, and , which are their own inverses. We call these fixed points under inversion.

There are two more special points at and , such that:

and

Now, is not actually a real number and you can sometimes get into trouble treating it like one, but for our purposes today we can just pretend that it is.

Inverse of a Complex Number

A complex number is usually written as . It has a length given by:

And an angle given by:

Its inverse is defined just like before:

But having a complex number in the denominator of a fraction is hard to reason about. How can we pull that into the numerator so we can make sense of it?

A typical choice is to multiply both the numerator and denominator by the complex conjugate, :

These components separately control the length and angle of :

The component means the new length is the inverse of the old length, just as with real numbers.

The component means the direction is the same, but mirrored over the real axis.

Now that we have some idea of what to expect, we can play around with a complex number inverter to try and build some intuition:

Can you visually confirm that big numbers become small and that every number is mirrored over the real axis?

One cool property of complex inversion is that every point inside the unit circle gets inverted outside of the circle and vice versa, but every point on the unit circle stays on the unit circle.

Notice the two fixed points at and . It makes sense that fixed points can only occur on the real axis, since inversion mirrors over the real axis.

As a hint of things to come: What happens if you move your cursor along the vertical line with real value ? What path does the inverse trace out?

Conformal Mappings

To appreciate inversion of a circle we need to understand a little bit about conformal mappings.

For our purposes, a mapping is a function that turns one complex number into another:

For example:

or

There is also a convenient shorthand for mappings, , which is pronounced “maps to” and is used like this:

Which can also be used to define a mapping or illustrate specific properties of a particular mapping.

Conformal mappings have a special simplifying property: they locally preserve angles.

Locally preserving angles means that while the large-scale structure may change, the small-scale structure stays exactly the same but for scaling and rotation. That means any two lines which intersect at before the mapping will still intersect at after the mapping.

This also implies that any two lines which are parallel before the mapping are still parallel after the mapping, at least locally. Even though the mapping may warp straight lines into curves, if you zoom in close enough to any small neighboring line segments they are still locally parallel.

Said another way: Tiny squares before the mapping will still be tiny squares after the mapping, though they may be shifted, scaled, and rotated. Squares will not warp into rectangles or diamonds.

From this falls an equivalent definition of conformal: Circles before the mapping remain circles after the mapping, but for scale and translation. The sizes and locations of the circles may change, but circles never get squished into ovals. These definitions will all be important later.

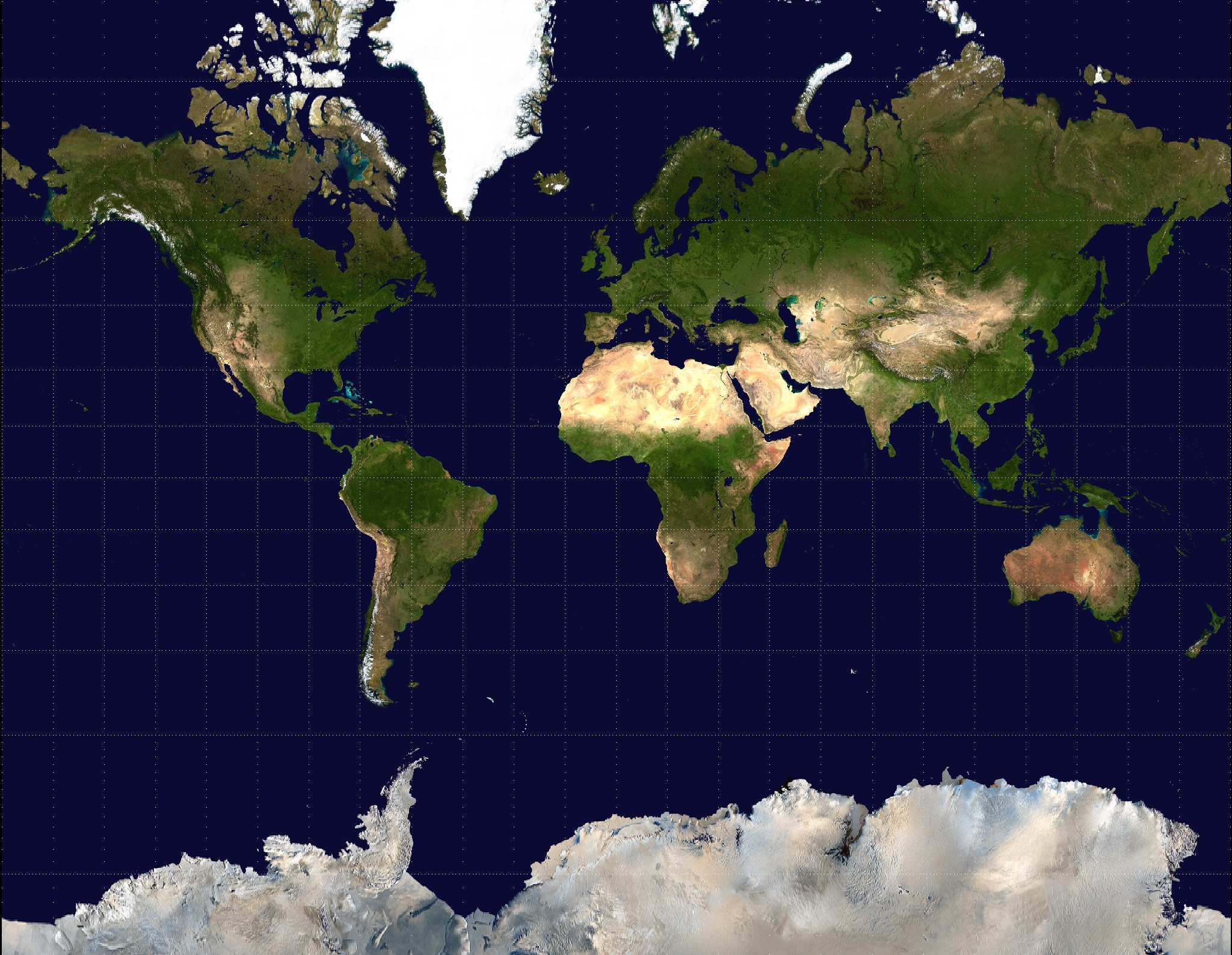

To test our understanding let’s examine a common mapping that transforms points on the Earth onto points in the complex plane, the Mercator Projection.

We call it a projection because we’re specifically mapping from a sphere to a plane, but it’s just a particular kind of mapping.

If the longitude is represented as and latitude is represented as , then the Mercator Projection is:

Is this mapping conformal? We can run a series of tests:

- Lines of constant Latitude (like the Equator, Tropic of Capricorn, etc) are all mutually parallel on the surface of the Earth. So too, in this projection.

- Lines of constant Longitude (like the Prime Meridian) are all mutually parallel on the surface of the Earth. Again, this is also true in this projection.

- Where Latitude and Longitude lines intersect, they do so at angles. This is also true after projection.

From these tests we can deduce that the projection is conformal!

There is another projection called the Stereographic Projection which is more useful for inverting circles:

The Stereographic Projection unwraps the Earth onto the 2D plane by placing the South Pole at the origin and stretching out the North Pole to according to:

Is the Stereographic projection conformal?

- Lines of constant Latitude are mutually parallel:

- Lines of constant Longitude are all mutually parallel:

- Lines of Latitude and Longitude are perpendicular:

So yes, this projection is also conformal.

A consequence of conformality is that any circle on the sphere of the Earth maps to a circle on the 2D plane. This is trivially true of the Equator, but how about the Prime Meridian, which has become an infinite line?

Well, the Prime Meridian passes through the North Pole which maps to the point at . That means the Prime Meridian, when projected onto the complex plane, must be a circle which includes the point , which means it must be a circle of radius , which looks like a line!

We can also look at the Stereographic projection in the opposite direction: Let’s wrap the entire complex plane onto a sphere such that the South Pole of the sphere touches the origin and the North Pole represents all the points that are infinitely far away from the origin.

If we’re careful, we can do this in just such a way that the unit circle in the complex plane maps to the sphere’s equator. This object is called the Riemann Sphere:

If you flip back and forth between the Riemann Sphere and the Stereographic projection image you may be able to convince yourself that they are in fact two descriptions of the same mapping.

Qualitatively: All the small complex numbers (magnitude ) are in the Southern hemisphere and all the big complex numbers (magnitude ) are in the Northern hemisphere.

The surface of the Riemann Sphere contains the entire complex plane so it is reasonable for us to ask: What does complex inversion look like on this surface?

The answer is easy to visualize:

A point on the complex plane is first mirrored across the equator to . This transforms the magnitude from something small to something large.

Then is mirrored across the real meridian, finally arriving at .

These two mirroring operations correspond exactly with the two components of complex inversion, derived above:

With this new picture in mind, try to visually walk through the known special cases from earlier:

- Fixed points at and

Now that we’ve got some 3D intuition for complex inversion on the Riemann Sphere, we’re ready to tackle the full problem.

Inverse of a Circle

Given that the Stereographic Projection is conformal, we know that a circle on the complex plane maps to a circle on the Riemann Sphere and vice versa.

Reflection across the unit circle preserves the shape of the circle, it just moves it from one hemisphere to the other.

By that same logic, mirroring across the real meridian also preserves the shape of the circle.

Finally, mapping that circle back to the complex plane is performed using the inverse of the Stereographic Projection, which must also be conformal.

In short:

The inverse of a circle on the complex plane must be another circle on the complex plane.

Qualitatively: Small circles close to the origin invert to big circles far from the origin and vice versa. Circles above the real line invert to circles below the real line and vice versa.

The symmetry of the Riemann Sphere now lets us identify some special cases:

- A circle centered on or is its own inverse

- A circle centered on inverts to a circle with the same radius, centered on

Points 1 and 2 are easily confirmed by simulation, but now we have a rich visual understanding of why they occur:

But wait, placing the cursor at does not create a circle which is its own inverse! We need to travel out to something like for the inverse to match. What gives?

The issue here is that a circle centered on on the Riemann Sphere does not translate to a circle centered on in the complex plane:

When projected onto the complex plane, the circle pictured must contain and its left side must fall between and , but its right side could extend very far out into extremely large numbers. The larger the radius of the circle, the larger the offset between the centers.

This is a subtle point that is worth rehashing. The exercise we did above where we reflected a circle across the equator (unit circle) and then again across the real meridian (real axis), all of that is correct both for the points on the circumference of the circle and for the midpoint of the circle once it lives on the Riemann Sphere. We just need to remember that while the Stereographic Projection preserves the shapes of circles, it does warp the space inside them such that their midpoints are not usually preserved!

Now consider a circle that touches the origin:

A circle that touches the origin inverts to a circle that passes through !

In order for a circle to pass through , it must stretch to the edge of the complex plane. It must be a circle of infinite radius, which looks like a straight line!

We saw this phenomenon as a special case earlier with the Prime Meridian and the Stereographic Projection, but here it appears as a general rule: any circle that touches the origin will invert to a line, not just meridians.

In this case we know that line passes through and that it approaches in a manner parallel to the imaginary axis, so this straight line must be a vertical line that passes through . Scroll back up to the simulation to confirm this for yourself!

Let’s put a bow on this topic by identifying a few more fixed points, or should we call them fixed circles?

- The unit circle inverts to itself

- The real axis inverts to itself

- Any circle centered on or (on the Riemann Sphere, not the complex plane) inverts to itself. The imaginary axis is therefore its own inverse

So inversion of a circle has one infinite family of fixed circles: those parallel to the imaginary axis, and then two special outliers which happen to also be fixed.

Enriching the Structure of a Circle

Let’s say that our input circle is spinning clockwise.

We can then declare that all points locally on the right hand side of the circumference are inside the circle, so we’ll paint them orange.

On the complex plane we now have filled-in circles with arrows to indicate direction:

On the Riemann Sphere it will look like a dome:

Playing around, we can see that circles centered on are flipped inside out! Another way to say this is that their spin direction is reversed.

The filled-in unit circle is no longer the equator, it is the entire Southern Hemisphere on the Riemann Sphere. Under inversion it becomes the entire Northern Hemisphere! So this circle is no longer its own inverse.

The real axis is no longer the real meridian, it is the entire hemisphere closer to us in the diagram, which inverts to the entire hemisphere far from us. This circle too, is no longer a special “fixed circle”.

But the imaginary axis is still its own inverse! The half-plane to the right of the imaginary axis forms the Eastern Hemisphere on the Riemann Sphere, which inverts to itself.

By adding structure to the circle, the inversion function has lost two of its fixed circles!

Rotations on the Riemann Sphere

We’ve been visualizing complex inversion as two reflections but we can also view it as a single rotation about the axis:

Go ahead and verify a few identities to convince yourself that they all work out identically:

- Fixed points at and

- imaginary axis ↦ imaginary axis

- unit circle ↦ unit circle but not if it is filled in

- real axis ↦ real axis but not if it is filled in

Looking at it this way provides new insight. Rotation about the axis could also be called rotation in a plane perpendicular to the axis. One such plane passes through the entire imaginary axis.

So in a colloquial sense, complex inversion is a rotation in the imaginary plane. Any circle parallel to that plane (just look on the Riemann Sphere) must invert to itself because circles are invariant to rotation. Circles perpendicular to that plane will only invert to themselves if they lack handedness.

We’ve also stumbled on a tantalizing new question! What happens if we were to rotate about the axis, aka in the real plane?

Well, large numbers still become small numbers and vice versa, but it’s like we’re reflecting over the imaginary axis instead of the real axis.

This implies some different definition of complex inversion! Before, we were using:

But this new rotation corresponds to:

Which is not an operation that I’ve seen before! It models a Bizarro-World complex plane where the special properties of the imaginary axis have been taken away and instead granted to the real axis.

From this we can simulate a different but still perfectly reasonable definition of the inverse of a circle!

We can see in the simulation and on the Riemann Sphere that for this operation:

- The fixed points are

- The fixed circle is the real axis and any other circle centered on

That brings us to our last contender, a rotation about the axis, or a rotation in the plane defined by the unit circle:

Can you see what this operation does to complex numbers? Big numbers stay big and small numbers stay small. This type of complex inversion is only changing the direction of complex numbers.

On the complex plane, all we’re doing is rotating around the origin!

- Our fixed points are and

- Our fixed circle is the unit circle and any other circle centered on the origin

By inspection we can write out this inversion formula as:

The three definitions that we’ve come to all look unique but now we know that they are actually three members of the same family: They are all rotations of the Riemann Sphere!

Digging Deeper

I hope this post conveys a little bit of what math can feel like when you just go exploring. It’s not so much about equations and manipulation of symbols as it is about asking “what if” and then following through.

Speaking of, here’s some ways you can dive deeper:

What does it mean to rotate by on the Riemann Sphere? Is this a familiar operation viewed in a new light, or something new? Can you derive an explicit formula for it in all three planes?

What does it mean to rotate the Riemann Sphere by any arbitrary ? Can you derive an explicit formula, perhaps making use of the complex exponential ?

Can you generate one of the inversion formulas above using only the other two? What implications does this have?

On the Riemann Sphere, what happens if you reflect an odd number of times instead of an even number? What are the fixed points and circles of such an operation? What about with filled circles?

Are there any squares which invert to themselves? Does it matter if you just use the four corners of the square vs every point along its edges?

The field of math we’ve been playing in is called Complex Analysis. You can also learn more by picking up a book, playing around online, or just watch some videos on Youtube!

Contact me

I’m on Twitter at @mferraro89 and you can shoot me an email me at mattferraro.dev@gmail.com